By: Emily Stagename

Though it was written as a response to the Chicago indie music scene in the 90s, Exile in Guyville manages to encapsulate the female experience unlike any album from its time.

There’s a certain insecurity that comes from growing up in the wrong body. Knowing who you are, and who you want to be, in contrast to who society says you are. Being lost personally is one thing; having to justify your identity and the way you view the world is another. When I was at my most disillusioned, I turned to music as a way to escape. One evening, I gave the album Exile in Guyville a listen and I found myself stunned.

Liz Phair formatted her debut record as a response to the Rolling Stones double LP Exile on Mainstreet. Though this formatting choice often overshadows the album itself and isn’t too terribly important in understanding the album as a whole, it does reveal something interesting: if Mainstreet was an album about the rock and roll male experience, then Guyville acts as a triumphant response devoted to the female rock experience. Though the song-by-song isn’t essential, that narrative note is.

Though I wouldn’t say this album is a standard concept album, its conceptual nature comes from that premise. Liz analyzes ideals about femininity unflinchingly, and does so through her first person perspective. In a 2013 retrospective interview with Jessica Hopper, Phair succinctly described the passion behind the album: “Guyville is wrapped up in how the songs were written and in the way it was created and came about: It’s that girl, that girl having people say you can’t do this, you aren’t good enough to do this, you don’t know what you are doing.”

There are songs like “6’1”, “Help Me Mary”, and “Dance of The Seven Veils” that are written about Liz Phair’s issue with low-bro, sexist men in a way that relies heavily on symbolism and simplicity to further their impact, which is a song-writing tactic that Liz excels at.

It should be noted that the honesty this album portrays goes both ways; Liz’s straightforward songwriting often paints her in a light that’s just as dysfunctional as those around here. The simplicity of “Fuck and Run” makes the heartbreaking and graphic subject matter seem normalized, and the strained delivery Liz gives to the track is exceptionally effective. “Flower”, a track that’s possibly the album’s magnum opus, uses an off-putting backing instrumental to discuss passionate lust, blankly and without hesitation. The self commentary about Liz’s interest in emotionally underdeveloped men is drowned out by the intensity of her interest in them (as is often the case in real life.) Though her honesty can be confrontational, Liz Phair never loses her ability to make that honesty enduring.

There is a lot that can be said about this album, both in terms of execution and conception. It was a modest enough critical success to become a defining work of mainstream indie rock, which led to a now dead wave of female indie darlings having their stake on the Billboard charts. Though what feminity is may be hard to quantify, Liz’s ability to dissect it in a way that stayed true to herself but still managed to carry a narrative helped lead me down the path of discovery that I will never forget. In a time like this, an album that’s uncompromisingly feminine is a great escape.

Interview conducted by Jessica Hopper for Spin magazine, June 2013.

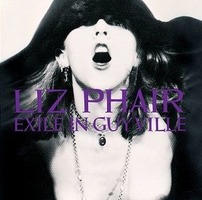

Photo credited to Matador

Leave a comment