By: Emily Stagename

In an attempt to rebel against artistic stagnation, a fed up Neil Young wrote the multifaceted masterpiece Rust Never Sleeps.

By 1979, Neil Young was at his wits end. The 70s were filled with commercial failures, mixed reviews, and infighting within his close circles. In an interview with Cameron Crowe of Rolling Stone, Young said this of his waning success: “I’ve got a job to do. The Eighties are here. I’ve got to just tear down whatever has happened to me and build something new. You can only have it for so long before you don’t have it anymore. You become an old-timer . . . which . . . I could be . . . I don’t know.” By the end of 1979, he took this promise to heart.

Rust Never Sleeps is a collaboration between Neil Young and the backing band Crazy Horse. The album, which is composed of an A side of acoustic tracks and a B side of electric tracks, was a big gamble. Though the acoustic fair was common for Young, the electric was not. With help from punk veteran Mark Mothersbough, Neil ventured into territory that’s now seen as proto-grunge, with explosive bass guitar, furious drumming, and syrupy vocals. The album was also formed primarily with live recordings, leading to instances of crowd feedback that made the acoustic sections feel more cozy and the electric more grandiose.

Beyond aesthetics, the record truly shines with Neil’s almost godlike ability to write multi-faceted, emotionally piercing lyrics. The fear of ‘rust’, of ‘not having it anymore’, is a dominant theme, both with regard to himself and peers. The album’s triumphant opener and closer (which are the same lyrically but played acoustically and electrically, respectively) tackle this theme bluntly. The songs parrot Young’s fears of being left behind, with a triumphant chorus to tie those thoughts together: “Hey, hey / my, my / rock and roll can never die.”

The album’s themes extend beyond artistic stagnation. Songs like “Thrasher”, “Powderfinger”, and “Pochahontas” use references to the history of Indigenous people’s treatment in America to comment on modern society, in a way that pays earnest tribute to the atrocities committed. “Pochahontas” in particular features a powerfully delivered performance, with a focus on isolation in its lyrics. The song inflicts an unconventional lyrical style that shifts times, tones, and subject matter quickly, to emphasize the disorienting nature of the attacks discussed.

As the album drew to a close, and Neil repeated the message given in the first song, I found myself fixated on one lyric: “And once you’re gone / you can’t come back / when you’re out of the blue / and into the black.” In comparing rock and roll to life and death, in pushing the boundaries of what a live album can be, and in using experimental lyrical technique, Neil Young exposes his fear of being replaced as blatantly as he could, and fights against this by playing his heart on every song. As the final notes of the album ring out, and the band is greeted to a mountain of applause, you start to wonder if that fear was ever justified. (Quote derived from Rolling Stone, as conducted by Cameron Crowe in 1979.)

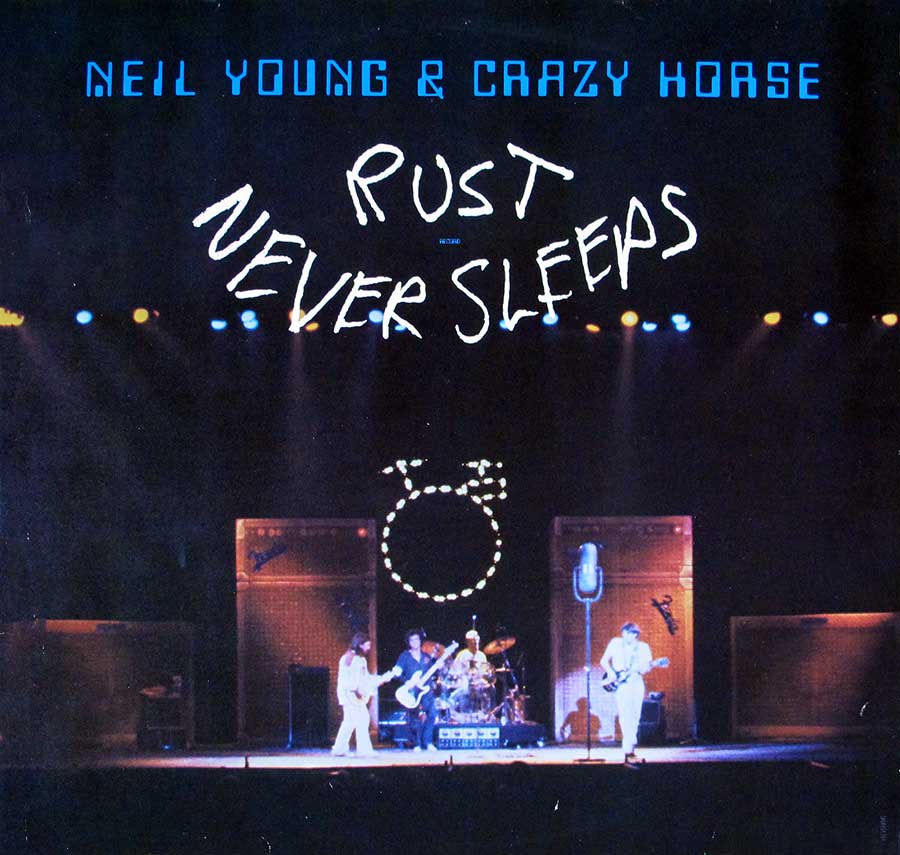

Photo credited to Reprise Records

Leave a comment